Research Article

Emergency laparoscopic left sided colonic resection with primary anastomosis: Feasibility and Safety

Mohamed Abdelhamid1*, AM Rashad1, MA Negida2, AZ Garib3, SS Soliman4 and TM EL-Gaabary4

1Surgery Department, Faculty of Medicine, Beni Suef, Egypt2Surgery Department, Faculty of Medicine, Kasr El Aini, Egypt

3Surgery Department, October 6th Faculty of Medicine, Giza, Egypt

4Surgery Department, Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum Egypt

*Address for Correspondence: Mohamed Abdelhamid, Surgery Department, Faculty of Medicine, Beni Suef, Egypt, Tel: 00201062531899; Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 09 November 2018; Approved: 19 November 2018; Published: 20 November 2018

How to cite this article: Abdelhamid M, Rashad AM, Negida MA, Garib AZ, Soliman SS, et al. Emergency laparoscopic left sided colonic resection with primary anastomosis: Feasibility and Safety. Arch Surg Clin Res. 2018; 2: 031-038. DOI: 10.29328/journal.ascr.1001021

Copyright License: © 2018 Abdelhamid M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery had a lower incidence of major complications, such as anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal bleeding, abscess, and evisceration. Controversies about the operative management of left colonic emergencies are decreasing. Nowadays there is worldwide shifting towards primary resection, on table lavage and primary anastomosis. The aim of this study is to record the safety of laparoscopic primary anastomosis in left-sided colonic emergencies.

Patients: The study was carried out at Beni-Suef University Hospital, in the period between January 2016 and July 2017. Twenty-six patients were included in this study, twelve with left colon cancer, twelve with left colonic complicated diverticulitis and two cases with sigmoid volvulus. Patients presented clinically with either obstruction or perforation. All patients were subjected to laparoscopic resection, on table lavage and primary anastomosis.

Method: Decompression was done prior to starting the intervention, followed by resection and on table lavage then colorectal anastomosis using the circular stapler. The study was approved by the ethical committee in the faculty.

Results: Mean operative time: 185 min (160- 245).

LOS: 12 (10- 18).

Leak: one in obstruction group and two in perforation group.

Redo one in perforation group.

Conclusion: Emergency laparoscopic left-sided colonic resection and primary anastomosis can be performed with low morbidity, however with caution if there was free perforation with peritonitis

Introduction

Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery had a lower incidence of major complications, such as anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal bleeding, abscess formation and evisceration [1]. Port-site metastasis and incomplete oncologic clearance are two gross concerns which challenge the safety of laparoscopic procedures. Recent studies showed a minimal port-site recurrence rate (<1%), comparable to open surgery. In this setting, the way of handling the specimen extraction has more influence than the surgical approach itself. Therefore, laparoscopic surgery is now considered to be safe in this regard [2]. Indeed, in a randomized controlled trial of elective surgery for diverticulitis, patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery had a lower incidence of major complications, such as anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal bleeding, abscess formation and evisceration [1].

The surgical management of left-sided large bowel emergency patients still remains controversial. There has been an increasing trend towards primary reconstruction surgery, yet the main dilemma remains about the appropriate patient selection for primary anastomosis [3]. Resection and primary anastomosis when correctly indicated, and in the hands of an expert surgeon, gives complications and mortality rates similar to the staged surgical procedure, yet gives a better life quality [4]. In patients requiring emergency colonic resection, intraoperative antegrade colon lavage with primary anastomosis, as described by Dudley in 1983, represents a safe alternative to the staged procedure, achieving an excellent mechanical bowel toilette that allows a safe anastomosis and avoids the disadvantages associated with the multiple staged operations [5]. Large bowel obstruction is due to colorectal carcinoma in 90% of cases. The optimal management of obstructing left colonic carcinoma still remains a controversial issue. In cases of obstructing left colorectal cancer, an experienced skilled surgeon can perform one stage resection anastomosis on patients with good general condition [6]. Emergency primary anastomosis in left-sided disease can be performed with a low morbidity and mortality in selected patients, even in the presence of a free perforation with diffuse peritonitis. Patients selected for staged resection are those with major comorbid disease [3].

Primary resection and anastomosis without a protective stoma have become the treatment of choice in uncomplicated diverticulitis. Primary resection and anastomosis may also be performed for perforation with localized pericolic or pelvic abscess. A single stage procedure is associated with a decreased hospital stay, and, also has lower mortality and morbidity compared with two stage and three stage procedures [7]. A grading system for the degree of perforation associated with diverticulitis has been revised by Hinchey et al. Stage I involves diverticulitis associated with pericolic abscess, stage II involves diverticulitis associated with distant abscess (retroperitoneal or pelvic), stage III involves diverticulitis associated with purulent peritonitis, and as to stage IV it involves diverticulitis associated with fecal peritonitis [8]. Primary resection with intraoperative colonic lavage compares favorably with Hartmann’s procedure for diffuse purulent peritonitis in complicated diverticulitis. Thus, primary resection with intraoperative colonic lavage should be an alternative to Hartmann’s procedure in stercoral peritonitis [9].

Patients

Twenty-six patients have been included in the current study. All patients were left-sided colonic emergencies presenting at Beni-Suef University Hospital during the period between January 2016 and July 2017. All patients were admitted as emergency cases, subjected to detailed history, physical examination and laboratory and radiological examinations. Resuscitation, nasogastric decompression, correction of any abnormality and evaluation of any associated comorbidity were all undergone. Computed tomography was done selectively to confirm the diagnosis in equivocal cases.

Patients were separated into two main clinical patterns. Obstruction was the main presentation to the left-sided colonic emergencies below the splenic flexure, while perforation or leak was the presentation of the other clinical pattern. It was defined as localized if there was a pericolic abscess, pelvic abscess or retroperitoneal collection (Hinchey I & II). It was defined as free if penumoperitoneum was evident on the abdominal x-ray film or if the feculent intra-peritoneal content was observed at operative exploration (Hinchey III & IV).

The research got approval from the ethical committee of our surgery department than got approval of the ethical committee of the Bani – Suef faculty of medicine. An informed consent is taken form every patient explaining the intervention and the other alternatives.

Methods

Operative procedures

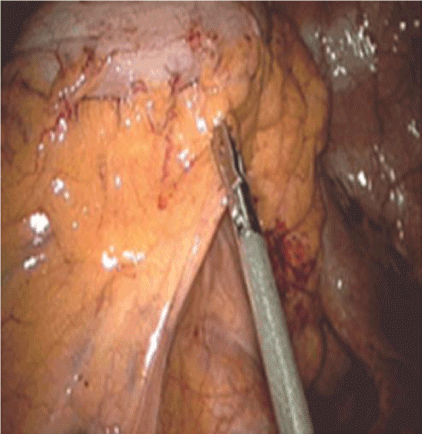

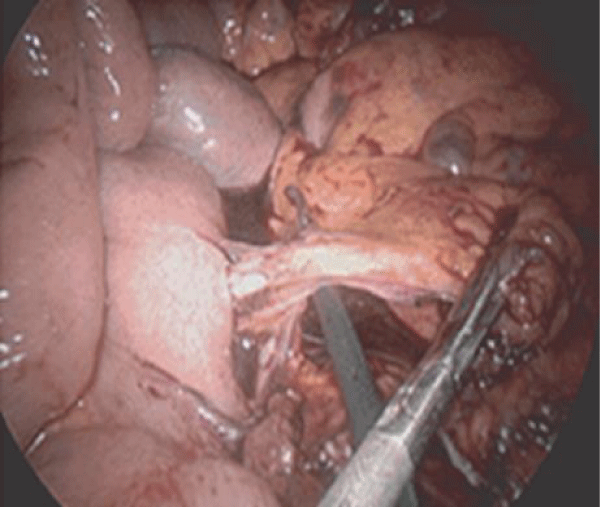

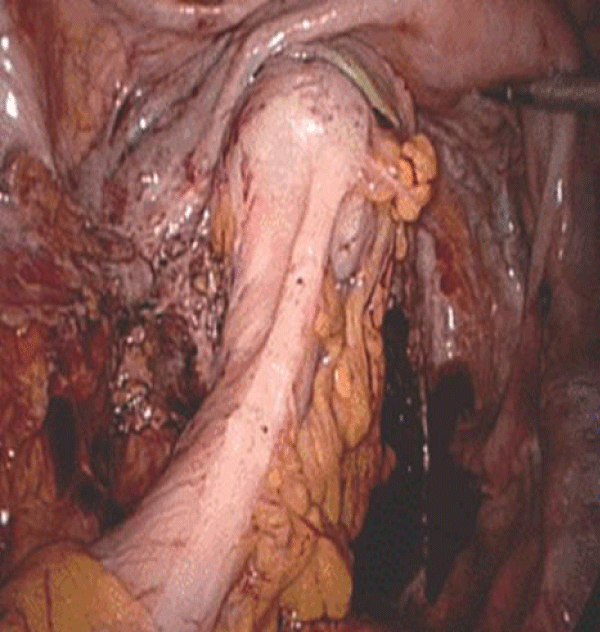

I. Bowel decompression was done once the abdomen has been entered, irrespective of the site of the lesion. The caecum was inspected to make sure a perforation has neither taken place nor was imminent, and a large Foley catheter was placed through the appendix stump. This was done in cases where the caecum was not hugely distended, and in cases where it was that a wide needle was inserted in a valvular manner proximal to the lesion to deflate the colon. This should be superficial to the fluid present in the colon to guard against needle obstruction. Dissection was performed in the majority of patients by bipolar vascular sealing devices (ligature device). Vessels were controlled with a bipolar vascular sealing device or metallic clips intra-corporeally in most circumstances.

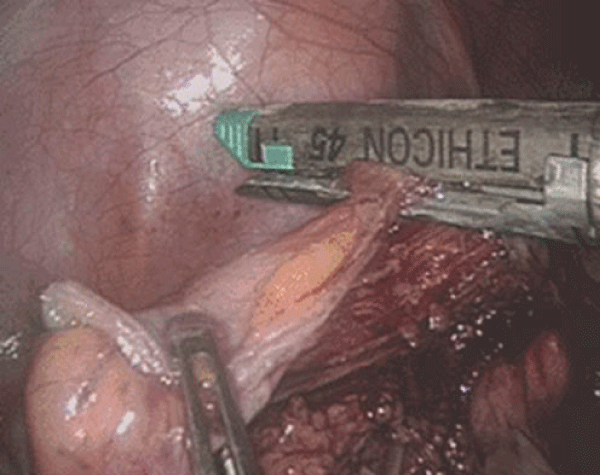

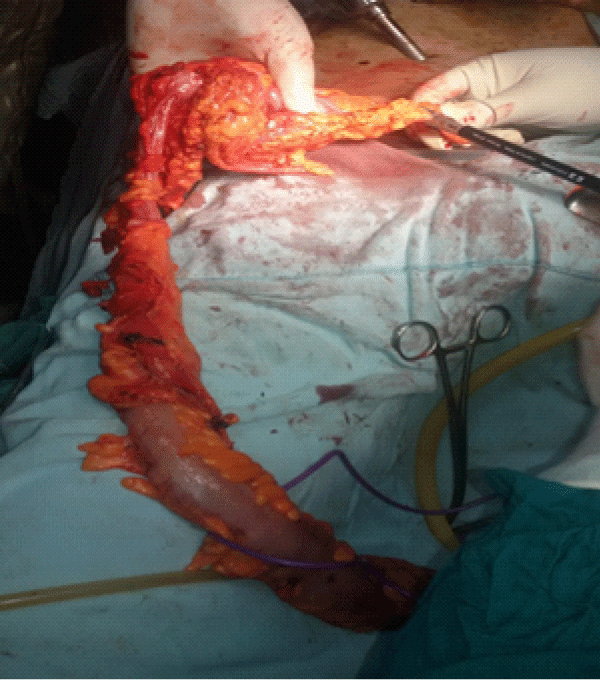

II. Dealing with the lesion, with a closure of the distal end with the straight stapler, and extraction of the specimen through a left iliac incision, with the delivery of the proximal cut bowel.

III. On table orthograde bowel lavage: A long length of pre-sterilized anesthetics scavenging tubing was attached very firmly to the proximal cut end. Normal saline was warmed to body temperature and then irrigated into the proximal colon through the Foley catheter.

IV. Cleansing of the distal segment: A proctoscope was passed into the anal canal and through it, a large Foley catheter was inserted. Normal saline was introduced through the Foley catheter to wash the lower segment.

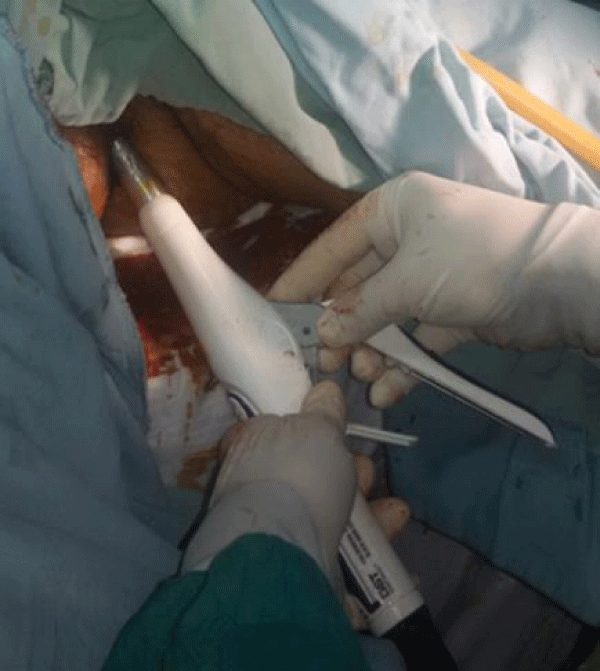

V. Primary anastomosis was done using the circular stapler (Figures 1-7).

Results

This study was conducted on 26 patients. Their age ranged from 32 years to 76 years. They were divided into groups according to operative data and histopathological examinations. The malignant group was 12 (46%) patients. The diverticulitis group was composed of 12 (46%) patients. The third group was composed of two (8%) patients with sigmoid volvulus (Table 1).

| Table 1: Patients classification. | ||

| Malignant | Diverticulitis | volvulos |

| 12 | 12 | 2 |

There were 16 (62%) patients presenting with a clinical picture of acute intestinal obstruction, two of which had sigmoid volvulus, three had an obstructed sigmoid mass, one had an obstructed rectosigmoid mass, eight had an obstructing mass in the descending colon and two had a diverticular obstruction without any peritoneal soiling. All diagnoses were confirmed histopathologically (Table 2).

| Table 2: Patients with obstruction. | |||||

| Total | Volvulos | Sigmoid mass | Rectosigmoid mass | Descending colon mass | Diverticuler obstruction |

| 16 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

The perforation cases were 10 (38%), all of which presented with a picture of acute abdomen. 7 perforation cases had local peritonitis, and another 3 had free perforations. Table 3 All 10 cases had complicated diverticulitis. Regarding the complications, in the obstruction group, there was one (6%) with a minimal leak which stopped on conservative treatment. Meanwhile, regarding the complications in the perforation group, there were two (20%) leaks, one of which was with local peritonitis which improved on conservative treatment, and the other case necessitated conversion to Hartmann. The mean operative time was 185 min (160- 245). The LOS was 12 days (10- 18). The incidence of a leak was one in the obstruction group and two in the perforation group.

| Table 3: Patients with perforations. | ||

| Total | Local peritonitis | Free peritonitis |

| 10 | 7 | 3 |

The redo incidence was one in the perforation group.

Discussion

To date, the operative strategy for left-sided large bowel obstruction remains controversial. Taking in consideration that a safe and definitive single-staged operation that avoids a colostomy, would definitely be in the patient’s best interest, every effort should thus be done to perform a primary anastomosis [10]. Once obstruction and perforation were considered as absolute contraindications to primary resection and anastomosis, yet, the paradigms in the surgical management of obstruction and perforation of the left colon are changing. In the older age group, left-sided colonic emergency cases usually present with many comorbid diseases [11].

Left-sided colonic emergencies due to complicated diverticulitis comprised 46% of all emergencies, while 46% left-sided colonic emergencies were due to complicated malignant disease of the left side, and 8% of the emergencies were due to sigmoid volvulus. Meanwhile, Meyer et al. [16], reported emergencies which were due to complicated diverticular disease in 33.4% of cases, and emergencies which were due to cancer left side in 66.6 % of cases.

In the current study, obstruction comprised 62% (16 cases) of left-sided emergencies, while perforation comprised 38% (10 cases) of left-sided emergencies, of which seven cases (70%) were focal and three cases (30%) were a free perforation.

Also, in the current study, complicated diverticulitis represented 46% of left-sided colonic emergencies, while its incidence was 33.4% in the study of Meyer et al. [16]. Meyer et al., also reported that 44.4% of cases in their study had a local perforation, 22.2% of cases had free perforation and 33.3% of cases had obstruction by the inflammatory process. Meanwhile, in our current study, 17% (2 cases) were due to obstruction, 58% (7 cases) were due to local perforation (Hinchy I, II) and 25% (3 cases) had a free perforation (Hinchy III, IV). Trillo et al. [17], reported 76.5% of cases were due to perforation, 15.7% of cases were due to obstruction and 7% of cases were due to hemorrhage, which was not encountered within our current study.

From the practical point of view, left-sided colonic emergencies should be classified as perforating or obstructive. All the same, in many situations of this current study, it was difficult to give an accurate diagnosis through the conventional preoperative diagnostic tools, and even by computed tomography. This was most obvious and pronounced in diverticular obstruction, which mimics to a great extent malignancy. This condition called for a need for histopathological examination to do this differentiation. Thus, the patients were accordingly classified into two main groups, an obstruction group which was compromised of 16 cases (62%) and a perforation group which was compromised of 10 cases (38%). This pattern is almost equivocal to that of Meyer et al. [16], who reported that the incidence of obstruction cases was 72.3%, and incidence of perforation cases was 27.7%. Still, Biondo et al. (18), reported an equivocal incidence of 45% peritonitis cases and 55% of obstruction cases. On the other hand, our study showed that 87.5% of obstruction cases was due to non-diverticular causes and 12.5% of the obstruction cases were due to diverticular complications. These findings were similar to those of Meyer et al. [16], who reported an 84.5% incidence and 15.3% incidence respectively.

Anastomotic leak was recorded clinically in 3 cases (11.5%). One anastomotic leak was in the obstruction group of patients, and it was a minimal leak that stopped on conservative treatment. Two anastomotic leaks were in the perforation group of patients, one of which was with the local perforation group and did well on conservative treatment, while the other was with the free perforation group and necessitated conversion to Hartmann.

Some coworkers stated that even resection and primary anastomosis can be performed safely without mechanical bowel preparation in sigmoid volvulus. Such a procedure has the merit of being a shorter and simpler procedure to perform, without any increasing morbidity or mortality [19]. Still, primary resection and anastomosis with manual decompression seem to be the procedure of choice [20].

Due to all the above-mentioned reasons, laparoscopic surgery has become the gold-standard procedure over the past decade. However, an increasing number of patients are still treated by sigmoidectomy and primary anastomosis, or by laparoscopic peritoneal lavage alone [21]. In addition to equivalent oncologic outcomes, multiple clinical trials have consistently shown lower peri-operative mortality rates. Multiple clinical trials have also shown fewer wound complications, less blood loss and reduced postoperative pain scores with a reduction in narcotic requirements after laparoscopic surgery. In spite of early concerns over port-site metastasis, cancer recurrence in wounds is reported to be similar to the 0–1% rates which are reported in open surgery. As laparoscopic lavage was not superior to sigmoidectomy, with regard to long-term major morbidity and mortality, other strategies such as laparoscopic sigmoidectomy need to be investigated [22]. Lately, the laparoscopic approach for generalized peritonitis is gaining acceptance for an increasing number of indications including cholecystitis, appendicitis, perforated peptic ulcer and small bowel obstruction [23]. Still, many surgeons regard general peritonitis, and especially fecal peritonitis, as a contraindication for a laparoscopic approach. This belief is related to a hypothetical risk of increased bacteremia and hypercapnia resulting from the pressure of the pneumoperitoneum [24]. Such a theory has neither been verified nor invalidated, but the experience gained with laparoscopic treatment in abdominal sepsis of various causes does not back this hypothesis [25].

Conclusion

Emergency laparoscopic left-sided colonic resection and primary anastomosis can be performed with a low morbidity but with caution in the presence of a free perforation with peritonitis, although it is linked with a high cost.

References

- Lee SY, Kwon HJ, Cho JH, Oh JY, Nam KJ, et al. Emergency laparoscopic left sided colonic resection with primary anastomosis: Feasibility and Safety mimicking appendiceal tumor: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16: 395-397. Ref.: https://goo.gl/mdd1aw

- Lisa-Gracia M, Martin-Rivas B, Pajaron-Guerrero M, Arnaiz-Garcia A. Abdominal actinomycosis in the last 10 years and risk factors for appendiceal actinomycosis: review of the literature. Turk J Med Sci. 2017; 47: 98-102. Ref.: https://goo.gl/FLcTkt

- Liu K, Joseph D, Lai K, Kench J, Ngu MC, et al. Abdominal actinomycosis presenting as appendicitis: two case reports and review. Journal of surgical case reports. J Surg Case Rep. 2016; 2016. Ref.: https://goo.gl/mh65Nd